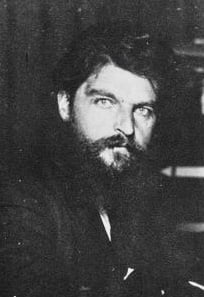

You probably haven’t heard of Nicolo Bombacci. I hadn’t. But his life was an interesting one. In fact it was almost a real time example of the Chinese line about “living in interesting times”. He most certainly did that.

Bombacci was born in rural poverty in the province of Romagna – the east side of Italy’s “thigh” – in 1879, and fell quite swiftly into the world of socialist politics. After briefly attending a seminary (like Stalin), he trained as a teacher, which was where he met another young socialist by the name of Benito Mussolini.

Leaving teaching in 1909, Bombacci devoted himself to politics, and quickly rose through the ranks, first in Trade Unionism and then as the socialist leader in Modena, emerging – by the end of World War One – as one of the national leaders of the Italian socialist movement, and being elected in 1919 to represent Bologna. From there, inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, he began to flirt with Communism; first suggesting Soviet-style “councils” in Italian politics, then visiting Soviet Russia in 1920 to participate in the second Comintern Congress. The following year, he became – alongside Antonio Gramsci – a founder member of the Italian Communist Party, and was even referred to as “the Lenin of the Romagna”. Predictably perhaps, during the Fascist “March on Rome” in October 1922, his house in the capital was ransacked – the contents thrown out onto the street and burned – and his secretary was subjected to the standard Fascist punishment of being forced to drink castor oil.

So far, one might imagine, so standard a trajectory. But for Bombacci, the rise of Fascism – and of his old friend Mussolini – changed things, made politics seem perhaps less tribal than it did for others. He didn’t abandon his left-wing positions – far from it; he even attended Lenin’s funeral in Moscow in 1924 – but, and in contrast to many of his fellows on the left, he insisted on viewing Fascism as an expression of those same principles that motivated him. Indeed, he would later claim that Lenin himself had told him that Mussolini had been the only serious socialist in Italy.

We are by now perhaps familiar with the old and occasionally heated arguments about the socialist origins of fascism – that Mussolini was originally a socialist, that Hitler supposedly marched in the funeral procession of communist Kurt Eisner in 1919, or that the “socialism” in “National Socialism” was anything more than eyewash – but Bombacci is the embodiment of that complex position. Indeed, in 1923, he even advocated a “union” of the two revolutions; the proletarian and the Fascist – in spite of the fact that so much of the popular support for Fascism in that period came from those who violently opposed Italy’s political left. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, such heresies led eventually to Bombacci’s defenestration; he was expelled from the Italian Communist Party in 1927 for “political unworthiness”.

Bombacci’s career then stalled into “the years of silence”, but by 1936 he was deemed sufficiently trustworthy – by Mussolini at least – to be permitted to establish a monthly political magazine called “La Verità” – riffing, no doubt, on “Pravda” – in which he could explain his positions. He did not waste time. Already in April 1936, he wrote that Mussolini’s experiment was: “a great social revolution” which was predicated upon “the triumph of work”. Fascism was no longer “just a doctrine”, he wrote, “it is a new order that boldly launches itself on the main path of social justice.”

Admittedly, Bombacci remained a rather fringe voice. Though he was accompanied on his political journey by other socialists, Fascism was characterised much more forcefully and vociferously by the old frothing Blackshirt blowhards like Roberto Farinacci or Achille Starace. Nonetheless, his day did come. After Mussolini’s fall in the autumn of 1943, he rose to prominence under the rump “Italian Social Republic” – commonly known as the “Republic of Salò” – which was established by Mussolini, in those areas still under German military occupation in September of that year.

Under the new Fascist rump state, Bombacci found a position as one of Mussolini’s closest advisors, and was even referred to as “the eminence grise of Salò”. So, while Fascism descended into what is generally considered to be its most radical phase, Bombacci was advising his Duce and defending the regime because he saw it as defending the rights of Italian workers. Few of his fellows on the left would have concurred. Indeed, he was lambasted as a turncoat and a traitor, for some even worse than Mussolini. Yet, he was unabashed. Answering his critics, he said in a speech in 1945: “You ask if I am the same socialist, communist, agitator, a friend of Lenin, from twenty years ago? Yes. I am the same person. I have never renounced the ideas I fought for and if God allows me to live for a little longer, I will continue to fight.”

God did not grant Bombacci’s wish. He was in the car alongside Mussolini, on 27 April 1945, when it was stopped by Communist partisans at Dongo, on Lake Como. The following day, the Duce‘s 15-strong entourage, including Bombacci and Mussolini’s mistress Clara Petacci, were taken to a nearby village and executed by firing squad. The day after that, their bodies were taken to Milan, where five of the most prominent among them were displayed to the Italian public; strung up by the heels from the remains of a garage forecourt on the Piazzale Loreto. Clara Petacci was in the centre, her modesty preserved by a neatly placed skirt. Mussolini was to the left of her, bare-chested, as so often in his propaganda. To the left of him was the body of Nicolo Bombacci.

To many, Bombacci travelled the full breadth of the political spectrum; from consorting with Lenin in the Soviet Union’s early days to dying alongside Mussolini twenty five years later. In truth, his was a most remarkable journey. But one has to wonder if the spectrum that he travelled across was really that broad. Horseshoe theory holds that the political spectrum should not be seen in linear terms; with the far left and the far right as far away from one another as can be. Rather it is more helpful to see that spectrum as a horseshoe, with the two extremes close together, but far from the middle ground of liberal democracy. It is very tempting to see Nicolo Bombacci as the poster-boy of that idea. For him, the journey from Communism to Fascism was a controversial one, and was certainly not without its perils, but – in his own mind at least – it was never much of a distance.